The Risk Riddle: Why False Precision Breaks Risk Management

The leadership team is deadlocked. Two risks, both representing $10M in annual expected loss, yet they can't agree on priorities. It's a modern version of Buridan's Ass: the philosophical paradox where a donkey starves between two equally appealing piles of hay, unable to choose.

A donkey, paralyzed between equal choices, dies from indecision; a paradox posed by philosopher Jean Buridan.

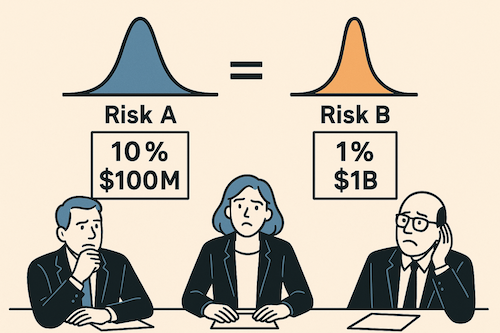

But here's the twist: these risks aren't actually identical. When we break it down a little further, we see:

Risk A: Data breach with 10% annual probability and $100M impact

Risk B: Regulatory shutdown with 1% annual probability and $1B impact

The math is identical. Both represent $10M in annualized risk. Yet watch what happens when you ask different stakeholders which risk keeps them up at night.

The Predictable Split

The CEO immediately points to the regulatory risk: "That's an existential threat to our business. We need a crisis management plan."

The CISO dismisses it entirely: "The data breach is the clear and present danger. That's where we need to focus our resources."

The Chief Risk Officer sighs: "Same math, totally different priorities. This is exactly why our risk discussions go in circles."

Same mathematical risk. Completely different reactions. Welcome to the Risk Riddle.

The False Precision Trap

Here's the problem: those point estimates are misleading. When we say "10% probability" and "$100M impact," we're creating an illusion of precision that doesn't exist in the real world.

The CEO's gut reaction isn't irrational; it's responding to uncertainty that our models hide. That "1% regulatory shutdown probability" could realistically range from 0.1% to 5%, depending on regulatory climate, pending investigations, and compliance posture. The impact could span $500M to $2B depending on timing, customer contracts, and recovery options. For existential risks, those uncertainty bounds matter enormously.

Similarly, the CISO knows that "10% data breach probability" is meaningless without context. Is that with current security controls, or after the planned infrastructure upgrade next month? During peak attack season? The range might actually be 3% to 25%, and crucially, it's something they can influence through action. The impact varies just as wildly; the incident response team could catch it mid-exfiltration and limit the blast radius, or they might not detect it for months while the FTC decides to throw the book at the company and make an example.

When Averages Lie

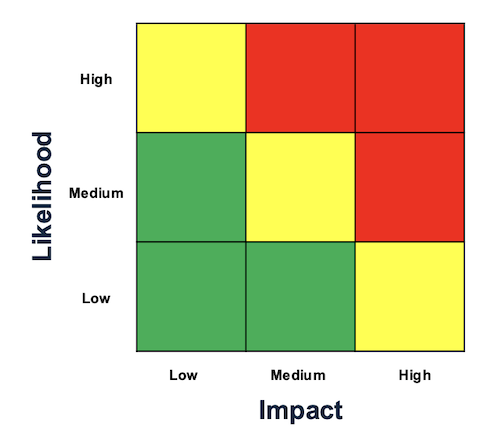

Red-yellow-green matrices collapse complex, multidimensional uncertainties into deceptively simple outputs

Traditional risk assessment, whether through red-yellow-green matrices or precise probability calculations, collapses complex, multidimensional uncertainties into deceptively simple outputs. Risk matrices reduce everything to "High-Medium-Low," while quantitative models that produce point estimates create an illusion of precision.

First, it misaligns stakeholder responses. The CEO sees "1% regulatory risk" and thinks "catastrophic tail risk with massive uncertainty." The CFO sees the same number and thinks "acceptable probability, let's buy insurance."

Second, it obscures actionability. A "10%" data breach risk means nothing without understanding the uncertainty range and what drives it. Are we 95% confident it's between 8-12%? Or could it realistically be anywhere from 2-30%?

Third, it prevents meaningful risk conversations. When you present point estimates, discussions devolve into debating whether the probability is "really" 10% or 12%. The more important strategic questions - risk appetite, response options, acceptable uncertainty levels - get lost.

The Distribution Solution

The answer isn't abandoning risk analysis. It's embracing the uncertainty that already exists.

Instead of "10% probability, $100M impact," express it as ranges:

Data breach: "We're looking at about 10% probability as our best estimate, though it could realistically range from 5% to 15%. Impact-wise, we're modeling around $100M typically, but we could see anything from $50M to $200M depending on how bad it gets."

Regulatory shutdown: "This one's much less likely - we're thinking around 1% probability, but the uncertainty is huge, anywhere from 0.1% to 3%. The scary part is when it hits, we're probably looking at $1B in losses, potentially ranging from $500M to $2B depending on scope and timing."

All of a sudden, we're having much more interesting conversations about where to apply our resources: what to cover with insurance, where to buy down risk, how much capital we need to make sure we have to cover these events, where we need to invest in mitigation versus resiliency. We've upgraded our conversations from arguing about ALEs to something much richer.

The data breach has higher likelihood of crossing our pain threshold, but the regulatory shutdown has catastrophic tail risk that could dwarf our loss assumptions entirely.

Probabilistic Thinking in Practice

When you model risks as distributions rather than point estimates, several things happen:

Risk conversations improve. Instead of arguing about whether something is 8% or 12% likely, you're discussing acceptable uncertainty levels and response strategies across probability ranges.

Decision-making becomes more robust. You can stress-test strategies against the full range of possibilities rather than optimizing for a single scenario.

Stakeholder alignment emerges naturally. The CEO's focus on existential threats and the CISO's emphasis on controllable risks both become rational responses to properly expressed uncertainty.

Beyond the Riddle

The Risk Riddle reveals something fundamental about how humans process uncertainty. We don't think in point estimates—we think in ranges, possibilities, and scenarios. When our risk models don't match how we naturally reason about uncertainty, the models become obstacles rather than tools.

The solution isn't more sophisticated mathematics. It's honest acknowledgment of what we don't know and modeling that reflects reality's inherent uncertainty.

Moving from point estimates to uncertainty ranges requires fundamentally rethinking your risk process - how you collect data, build models, and structure conversations. It's not a quick fix, but organizations that make this shift find their risk discussions become genuinely strategic rather than debates over decimal places. The uncertainty was always there; now you're just being honest about it.

False precision doesn't just break risk models. It breaks the conversations that matter most.