Vendor Sales Tactics: The Good, The Bad, and the Bathroom

Most security vendors are great — but a few cross the line from persistent to downright creepy, sometimes in ways you won’t believe. With RSA Conference looming, here’s a behind-the-scenes look at the worst sales tactics I’ve ever seen (yes, even in the bathroom).

Source: AI-generated using ChatGPT

I’ve been in security for a long time. Over the years, I’ve held all kinds of roles: from leadership positions managing large teams with direct purchasing power to engineering roles with deep influence over what tools the organization buys to stay secure.

For this reason, I’ve been on the receiving end of a lot of vendor pitches. And let me say this up front: the vast majority of vendors are fantastic. I genuinely enjoy meeting with them, hearing what they’re building, and learning from their perspective. Many of them have become trusted strategic partners - some I’ve brought with me from company to company. A few have even become personal friends.

But… like in any field, there are occasional missteps. And sometimes those missteps are truly memorable.

With RSA Conference right around the corner, and since it happens right here in my backyard in San Francisco, I thought it’d be the perfect time to share a little perspective. So here it is:

My Top 3 Worst Vendor Sales Tactics of All Time

Ranked from “mildly annoying” to “seriously, please never do this again.” Yes, the last one actually happened. And no, I haven’t recovered.

1. Badge Scanning Snipers

Source: AI-generated using ChatGPT

Okay, this one kills me. I don’t know if this happens to everyone, but it’s happened to me enough that I’ve had to start taking proactive measures.

Picture the scene: you’re walking through the vendor expo at RSA, keeping your head down, doing your best not to make eye contact. A vendor rep steps into your path, smiles, and says “Hi!” I try to be polite, so I smile back. Then, without asking, they grab my badge off my chest and scan it.

No conversation, no context, no consent.

For those unfamiliar: conference badges often have embedded chips that contain personal contact info—name, email, phone number, company, title, etc. A quick scan, and boom - you’re in their lead database. You didn’t stop at their booth. You didn’t ask for follow-up. But congratulations, you’re now a “hot lead.”

Just like in Glengarry Glen Ross, once you're in the lead system, it's over. The emails and calls come fast and furious. You will know no peace.

My two best defenses:

Register with throwaway contact info. I still use my real name and company, but I use a burner email address and a Google Voice number.

Flip your badge around while walking the expo floor. If you have a prominent title or work for a big company, you’re basically bleeding in shark-infested waters. Don’t be chum.

Lead gen is part of the game. I get it. But consent matters. If you’re scanning without asking, it’s not clever - it’s creepy.

2. The Fake Referral Drop

Source: AI-generated using ChatGPT

This one happens so often it’s practically background noise—but it still annoys me just as much as the first time it happened.

Here’s how it goes: someone reaches out and says, “Hey, [Name] told me to contact you.”

Except… they didn’t. I double-check, and the person they named either never mentioned me, or they don’t even exist. It’s a made-up referral, used to lower my defenses and start a conversation under false pretenses.

It’s lazy, manipulative, and unfortunately still effective enough that people keep doing it.

Worse yet, there’s a close cousin to this move: The Fake Account Manager.

That’s when someone emails me saying, “Hi, I’m your account manager from [Vendor X]. When can we meet for 30 minutes?”

Naturally, I assume we’re already a customer. I even feel a little urgency—maybe I should know more about the product my company is using. But when I dig in, I find out: We’re not a customer. They’re not an account manager. It’s a bait-and-switch—pretending we already have a business relationship to trick me into a meeting.

This one isn’t just misleading. It’s dishonest. And it guarantees I won’t take you seriously again.

3. The Bathroom Pitch

Source: AI-generated using ChatGPT

Thankfully, this one only happened once—but that was enough.

It was RSA, maybe 2016 or 2017. I was between sessions and ducked into the restroom. I walked up to the urinal, doing what one does, and the guy next to me turns, makes eye contact (strike one), and says:

“Hey! I saw you in one of the sessions earlier and I tried to catch you after. Glad I ran into you in here!”

And then, while we’re both mid-stream, he launches into a pitch about his security product.

Let me paint the scene more clearly:

I am actively using a urinal.

He is actively using a urinal.

And he’s pitching me endpoint protection like we’re at a cocktail mixer.

I said maybe one word, washed my hands, and got out of there. It was in that moment I realized: There is no safe space at RSA.

Don’t ambush people in bathrooms. Also, don’t pitch while they’re eating or anywhere else people are just trying to be human for a moment. If your sales strategy involves cornering someone mid-pee, it’s not just bad sales - it’s bad humanity.

Wrapping It Up

Again, I want to emphasize: I love vendors. I love sales. Some of my strongest relationships in this industry have come from vendors.

This post isn’t about bashing the vendor community—it’s about calling out the 1% of behavior that makes it harder for the other 99% to do their job well. Sales is hard. Security buyers can be tough. But authenticity, respect, and honesty go a long way.

So if you’re at RSA this year: Let’s talk. Just… not in the bathroom, please.

A Beginner's Guide to Cyber War, Cyber Terrorism and Cyber Espionage

Cyber war, terrorism, espionage, vandalism—these terms get thrown around a lot, but what do they actually mean? This guide cuts through the hype and headlines to help you tell the difference (and finally stop calling everything “cyber war”).

Photo by Rafael Rex Felisilda on Unsplash

Tune in to just about any cable talk show or Sunday morning news program and you are likely to hear the terms “cyber war,” “cyber terrorism,” and “cyber espionage” bandied about in tones of grave solemnity, depicting some obscure but imminent danger that threatens our nation, our corporate enterprises, or even our own personal liberties. Stroll through the halls of a vendor expo at a security conference, and you will hear the same terms in the same tones, only here they are used to frighten you into believing your information is unsafe without the numerous products or services available for purchase.

The industry lacks a rubric of clear and standardized definitions of what constitutes cyber war, cyber terrorism, cyber espionage and cyber vandalism. Because of this, it’s becoming increasingly difficult for those of us in the profession to cut through the noise and truly understand risk. For example, on one hand, we have politicians and pundits declaring that the US is at cyber war with North Korea, and on the other hand President Obama declared the unprecedented Sony hack was vandalism. Who’s right?

The issue is exacerbated by the fact that such terms are often used interchangeably and without much regard to their real-world equivalents.

The objective of this article is to find and provide a common language to help security managers wade through the politicking and marketing hype and get to what really matters.

The state of the world always has been and always will be one of constant conflict, and technological progress has extended this contention from the physical realm into the network of interconnected telecommunications equipment known as cyberspace. If one thinks of private-sector firms, government institutions, the military, criminals, terrorists, vandals, and spies as actors, cyberspace is their theater of operations. Each of these actors may have varying goals, but they are all interwoven, operating within the same medium. What separates these actors and accounts for the different definitions in the “cyber” terms are their ideologies, objectives, and methods.

The best way to forge an understanding of the differences in terms is to look at the conventional definitions of certain words and simply apply them to cyberspace. For example, traditional, kinetic warfare has a clear definition that is difficult to dispute: a conflict between two or more governments or militaries that includes death, property destruction, and collateral damage as an objective. Cyber warfare, therefore, uses the same principles of goals, actors, and methods that one can examine against a cyber attack to ascertain the gravity of the situation.

Let’s examine two of the most common phrases used, “cyberspace” and “cyber attack” and get to the root of what they really mean.

The realm in which all of this takes place in cyberspace, and as previously stated, can be thought of as a theater of operation.

The Department of Defense defines cyberspace as:

A domain characterized by the use of electronics and the electromagnetic spectrum to store, modify, and exchange data via networked systems and associated physical infrastructures.

A good analogy to help people understand cyberspace is to draw a parallel to your physical space. You are a person and you are somewhere; perhaps an office, house, or at the car wash reading this on your iPhone. This is your environment, your space. You have objects around you that you interact with: a car, a sofa, a TV, a building. You are an actor in this space and there are other actors around you; most have good intentions, and some have bad intentions. At any point, someone in this environment can act against you or act against an object in the environment.

Cyberspace is essentially the same: it is an environment in which you operate. Instead of physically “being” somewhere, you are using computing equipment to interact over a network and connect to other resources that give you information. Instead of “objects,” like a car or a sofa, you have email, websites, games, and databases.

And just like real life, most people you interact with are benign but some are malicious. In the physical space, a vandal can pick up a spray paint can and tag your car. In cyberspace, a vandal can replace your website’s home page with a web defacement. This is called a cyber attack and the vandal is a cyber vandal.

The graphic below illustrates the overall cyberspace environment, threat actors, and possible targets. To help you conceptualize this, think about the same paradigm, but in a physical space. Take away the word “cyber” and you have warriors, terrorists, vandals, and spies that attack targets.

View of cyberattacks

The actual attack may look the same or similar coming from different threat actors, but goals, ideology and motivation is what sets them apart.

An excellent definition of an attack that occurs in cyberspace comes from James Clapper, former Director of National Intelligence:

A non-kinetic offensive operation intended to create physical effects or to manipulate, disrupt, or delete data.

This definition is intentionally very broad. It does not attempt to attribute political ideologies, motivations, resources, affiliations, or objectives. It simply states the characteristics and outcome.

Cyber attacks of varying degrees of destruction occur daily from a variety of actors and for many different reasons, but some high-profile attacks are the recent rash of retail data breaches, the Sony Pictures Entertainment hack, website vandalism, and distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks.

The groundwork is set for what is a cyber attack and the environment, cyberspace, in which they are launched and experienced by the victim. This is the first step in dispelling myths to truly understand risk and what is possible (and not possible) when it comes to protecting your firm and the nation.

Now the real fun begins — we’ll dissect the four most commonly confused terms: “cyber war,” cyber terrorism,” “cyber vandalism” and “cyber espionage” and provide a common lexicon. The objective is to dispel myths and, by establishing common understanding, provide a way for managers to cut to the chase and understand risk without all the FUD. The graph below shows the four terms and attributes at a glance.

Commonly used “cyber” terms and definitions

Now let’s dig into each individual definition and examine the fundamentals.

Cyber warfare

Cyber warfare is the most misused terms in this list. The U.S. Strategic Command’s Cyber Warfare Lexicon defines cyber warfare as:

Creation of effects in and through cyberspace in support of a combatant commander’s military objectives, to ensure friendly forces freedom of action in cyberspace while denying adversaries these same freedoms.

There are very clear definitions as to what constitutes war (or an action that is an act of war), and the cyber version is, in essence, no different. Cyber warfare is an action, or series of actions, by a military commander or government-sponsored cyber warriors that furthers his or her objectives, while disallowing an enemy to achieve theirs. Military commanders typically belong to a nation-state or a well-funded, overt and organized insurgency group (as opposed to covertrebels, organized crime rings, etc.). Acting overtly in cyberspace means you are not trying to hide who you are — the cyber version of regular, uniformed forces versus irregular forces.

On Dec. 21, 2014, President Obama stated that the Sony hack was an act of cyber vandalism perpetuated by North Korea, and not an act of war. This statement was criticized by politicians, security experts and other members of the public, but one must look at what constitutes an act of war before a rush to judgment is made. Let’s assume for the sake of this analysis that North Korea did perpetrate the attack (although this is disputed by many). Was the act part of a military maneuver, directed by a commander, with the purpose of denying the enemy (the United States) freedom of action while allowing maneuverability on his end? No. The objective was to embarrass a private-sector firm and degrade or deny computing services. In short, Obama is right — it’s clearly not part of a military operation. It’s on the extreme end of vandalism, but that’s all it is.

The subsequent threats of physical violence to moviegoers if they viewed “The Interview” has never been attributed to those who carried out the cyber attack, and frankly, any moron with Internet access can make the same threats.

Few public examples exist of true, overt cyber warfare. Stories circulate that the U.S., Israel, Russia, China and others have engaged in cyber war at some point, but the accounts either use a looser definition of cyber war, or are anecdotal and are not reported on by a reputable news source.

One of the strongest candidates for a real example of cyber war occurred during the 2008 Russo-Georgian War.

Georgia, Ossetia, Russia and Abkhazia (en)” by Ssolbergj (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Russia and Georgia engaged in armed conflict over two breakaway republics, South Ossetia and Abkhazia — both located in Georgia. Russia backed the separatists and eventually launched a military campaign. In the days and weeks leading up to Russia’s direct military intervention, hackers originating from within Russia attacked key Georgian information assets. Internet connectivity was down for extended periods of time and official government websites were hacked or completely under the attacker’s control. In addition, internal communications and news outlets were severely disrupted. All of the above would hamper the ability of Georgian military commanders to coordinate defenses during the initial Russian land attack.

Cyber terrorism

No one can agree on the appropriate definition of terrorism, and as such, the definition of cyber terrorism is even murkier. Ron Dick, director of the National Infrastructure Protection Center, defines cyber terrorism as

…a criminal act perpetrated through computers resulting in violence, death and/or destruction, and creating terror for the purpose of coercing a government to change its policies.

Many have argued that cyber terrorism does not exist because “cyberspace” is an abstract construct, whereas terror in a shopping mall is a very real, concrete situation in the physical world that can lead to bodily harm for those present. Cyber terrorism, as a term, has been used (and misused) so many times to describe attacks, it has almost lost the gravitas its real-world counterpart maintains.

According to US Code, Title 22, Chapter 38 § 2656f, terrorism is:

…premeditated, politically motivated violence perpetrated against noncombatant targets by subnational groups or clandestine agents.

In order to be a true cyber terrorist attack, the outcome must include violence toward non-combatants and result in large-scale damage or financial harm. Furthermore, it can often be difficult to attribute motivations, goals, and affiliations to cyber defilement, just as in the physical world, which makes attribution and labels difficult in the cases of both traditional terrorism and cyber-terrorism.

There are no known examples of true cyber terrorism. It certainly could happen — it just hasn’t happened yet.

Cyber vandalism

There is not an “official” US government definition of cyber vandalism, and definitions elsewhere are sparse. To paraphrase Justice Stewart, it’s not easy to describe, but you will know it when you see it.

The definition of “vandalism” from Merriam-Webster is “willful or malicious destruction or defacement of public or private property.”

Cyber vandals usually perpetrate an attack for personal enjoyment or to increase their stature within a group, club, or organization. They also act very overtly, wishing to leave a calling card so the victim and others know exactly who did it — think of wayward subway taggers, and the concept is about the same. Some common methods are website defacement, denial-of-service attacks, forced system outages, and data destruction.

Examples are numerous:

Anonymous DDoS attacks of various targets in 2011–2012

Lizard Squad DDoS attacks and website defacements in 2014

For now, the Sony Pictures Entertainment hack, unless attribution can be made to a military operation under the auspices of a nation-state, which is unlikely.

Cyber espionage

Much of what the public, politicians, or security vendors attribute to “cyber terrorism” or “cyber war” is actually cyber espionage, a real and quantifiable type of cyber attack that offers plenty of legitimate examples. An eloquent definition comes from James Clapper, former Director of National Intelligence:

…intrusions into networks to access sensitive diplomatic, military, or economic

There have been several high-profile cases in which hackers, working for or sanctioned by the Chinese government, infiltrated US companies, including Google and The New York Times, with the intention of stealing corporate secrets from companies that operate in sectors in which China lags behind. These are examples of corporate or economic espionage, and there are many more players — not just China.

Cyber spies also work in a manner similar to the methods used by moles and snoops since the times of ancient royal courts; they are employed by government agencies to further the political goals of those organizations. Many examples exist, from propaganda campaigns to malware that has been specifically targeted against an adversary’s computing equipment.

Examples:

The Flame virus, a very sophisticated malware package that records through a PC’s microphones, takes screenshots, eavesdrops on Skype conversations, and sniffs network traffic. Iran and other Middle East countries were targeted until the malware was discovered and made public. The United States is suspected as the perpetrator.

The Snowden documents revealed many eavesdropping and espionage programs perpetrated against both US citizens and adversaries abroad by the NSA. The programs, too numerous to name here, are broad and use a wide variety of methods and technologies.

Conclusion

The capabilities and scope of cyber attacks are just now starting to become understood by the public at large — in many cases, quite some time after an attack has taken place. Regardless of the sector in which you are responsible for security, whether you work at a military installation or a private-sector firm, a common language and lexicon must be established so we can effectively communicate security issues with each other and with law enforcement, without the anxiety, uncertainty and doubt that is perpetuated by politicians and security vendors.

The article was originally published at CSO Online as a two-part series (Part 1 and Part 2) and updated in 2022.

What’s the difference between a vulnerability scan, penetration test and a risk analysis?

Think vulnerability scan, pen test, and risk analysis are the same thing? They're not — and mixing them up could waste your money and leave you exposed. This post breaks down the real differences so you can make smarter, more secure decisions.

You’ve just deployed an ecommerce site for your small business or developed the next hot iPhone MMORGP. Now what?

Don’t get hacked!

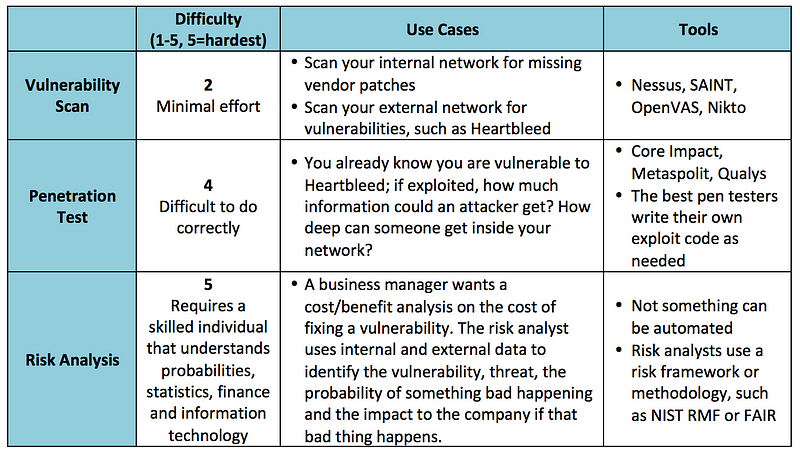

An often overlooked, but very important process in the development of any Internet-facing service is testing it for vulnerabilities, knowing if those vulnerabilities are actually exploitable in your particular environment and, lastly, knowing what the risks of those vulnerabilities are to your firm or product launch. These three different processes are known as a vulnerability assessment, penetration test and a risk analysis. Knowing the difference is critical when hiring an outside firm to test the security of your infrastructure or a particular component of your network.

Let’s examine the differences in depth and see how they complement each other.

Vulnerability assessment

Vulnerability assessments are most often confused with penetration tests and often used interchangeably, but they are worlds apart.

Vulnerability assessments are performed by using an off-the-shelf software package, such as Nessus or OpenVas to scan an IP address or range of IP addresses for known vulnerabilities. For example, the software has signatures for the Heartbleed bug or missing Apache web server patches and will alert if found. The software then produces a report that lists out found vulnerabilities and (depending on the software and options selected) will give an indication of the severity of the vulnerability and basic remediation steps.

It’s important to keep in mind that these scanners use a list of known vulnerabilities, meaning they are already known to the security community, hackers and the software vendors. There are vulnerabilities that are unknown to the public at large and these scanners will not find them.

Penetration test

Many “professional penetration testers” will actually just run a vulnerability scan, package up the report in a nice, pretty bow and call it a day. Nope — this is only a first step in a penetration test. A good penetration tester takes the output of a network scan or a vulnerability assessment and takes it to 11 — they probe an open port and see what can be exploited.

For example, let’s say a website is vulnerable to Heartbleed. Many websites still are. It’s one thing to run a scan and say “you are vulnerable to Heartbleed” and a completely different thing to exploit the bug and discover the depth of the problem and find out exactly what type of information could be revealed if it was exploited. This is the main difference — the website or service is actually being penetrated, just like a hacker would do.

Similar to a vulnerability scan, the results are usually ranked by severity and exploitability with remediation steps provided.

Penetration tests can be performed using automated tools, such as Metasploit, but veteran testers will write their own exploits from scratch.

Risk analysis

A risk analysis is often confused with the previous two terms, but it is also a very different animal. A risk analysis doesn’t require any scanning tools or applications — it’s a discipline that analyzes a specific vulnerability (such as a line item from a penetration test) and attempts to ascertain the risk — including financial, reputational, business continuity, regulatory and others — to the company if the vulnerability were to be exploited.

Many factors are considered when performing a risk analysis: asset, vulnerability, threat and impact to the company. An example of this would be an analyst trying to find the risk to the company of a server that is vulnerable to Heartbleed.

The analyst would first look at the vulnerable server, where it is on the network infrastructure and the type of data it stores. A server sitting on an internal network without outside connectivity, storing no data but vulnerable to Heartbleed has a much different risk posture than a customer-facing web server that stores credit card data and is also vulnerable to Heartbleed. A vulnerability scan does not make these distinctions. Next, the analyst examines threats that are likely to exploit the vulnerability, such as organized crime or insiders, and builds a profile of capabilities, motivations and objectives. Last, the impact to the company is ascertained — specifically, what bad thing would happen to the firm if an organized crime ring exploited Heartbleed and acquired cardholder data?

A risk analysis, when completed, will have a final risk rating with mitigating controls that can further reduce the risk. Business managers can then take the risk statement and mitigating controls and decide whether or not to implement them.

The three different concepts explained here are not exclusive of each other, but rather complement each other. In many information security programs, vulnerability assessments are the first step — they are used to perform wide sweeps of a network to find missing patches or misconfigured software. From there, one can either perform a penetration test to see how exploitable the vulnerability is or a risk analysis to ascertain the cost/benefit of fixing the vulnerability. Of course, you don’t need either to perform a risk analysis. Risk can be determined anywhere a threat and an asset is present. It can be data center in a hurricane zone or confidential papers sitting in a wastebasket.

It’s important to know the difference — each are significant in their own way and have vastly different purposes and outcomes. Make sure any company you hire to perform these services also knows the difference.

Originally published at www.csoonline.com on May 13, 2015.

Not all data breaches are created equal — do you know the difference?

Not all data breaches are created equal — the impact depends on what gets stolen. From credit cards to corporate secrets, this post breaks down the real differences between breach types and why some are much worse than others.

It was one of those typical, cold February winter days in Indianapolis earlier this year. Kids woke up hoping for a snow day and old men groaned as they scraped ice off their windshields and shoveled the driveway. Those were the lucky ones, because around that same time, executives at Anthem were pulling another all-nighter, trying to wrap their heads around their latest data breach of 37.5 million records and figuring out what to do next. And, what do they do next? This was bad — very bad — and one wonders if one or more of the frenzied executives thought to him of herself, or even aloud, “At least we’re not Sony.”

Why is that? 37.5 million records sure is a lot. A large-scale data breach can be devastating to a company. Expenses associated with incident response, forensics, loss of productivity, credit reporting, and customer defection add up swiftly on top of intangible costs, such as reputation harm and loss of shareholder confidence. However, not every data breach is the same and much of this has to do with the type of data that is stolen.

Let’s take a look at the three most common data types that cyber criminals often target. Remember that almost any conceivable type of data can be stolen, but if it doesn’t have value, it will often be discarded. Cyber criminals are modern day bank robbers. They go where the money is.

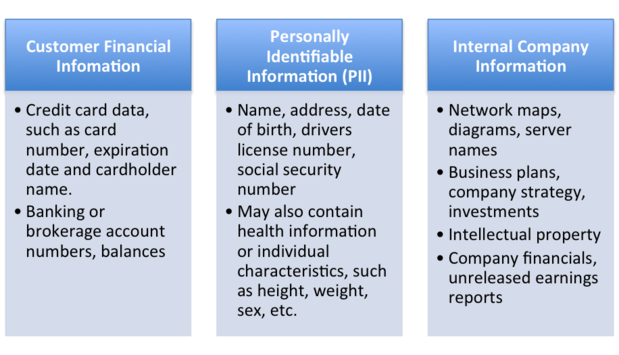

Common data classifications and examples

Customer financial data

This category is the most profuse and widespread in terms of the number of records breached, and mostly includes credit card numbers, expiration dates, cardholder names, and other similar data. Cyber criminals generally pillage this information from retailers in bulk by utilizing malware specifically written to copy the credit card number at the point-of-sale system when a customer swipes his or her card. This is the type of attack that was used against Target, Home Depot, Neiman-Marcus and many others, and incidents such as these have dominated the news for the last several years. Banks have also been attacked for information on customers.

When cyber criminals then attempt to sell this pilfered information on the black market, they are in a race against time — they need to close the deal as quickly as possible so the buyer is able to use it before the card is deactivated by the issuing bank. A common method of laundering funds is to use the stolen cards to purchase gift cards or pre-paid credit cards, which can then be redeemed for cash, sold, or spent on goods and services. Cardholder data is typically peddled in bulk and can go for as little as $1 per number.

Companies typically incur costs associated with response, outside firms’ forensic analysis, and credit reporting for customers, but so far, a large-scale customer defection or massive loss of confidence by shareholders has not been observed. However, Target did fire its CEO after the breach, so internal shake-ups are always a stark possibility.

Personally identifiable information

Personally Identifiable Information, also known as PII, is a more serious form of data breach, as those affected are impacted far beyond the scope of a replaceable credit card. PII is information that identifies an individual, such as name, address, date of birth, driver’s license number, or Social Security number, and is exactly what cyber criminals need to commit identity theft. Lines of credit can be opened, tax refunds redirected, Social Security claims filed — essentially, the possibilities of criminal activities are endless, much like the headache of the one whose information has been breached.

Unlike credit cards, which can be deactivated and the customer reimbursed, one’s identity cannot be changed or begun anew. When a fraudster gets a hold of PII, the unlucky soul whose identity was stolen will often struggle for years with the repercussions, from arguing with credit reporting agencies to convincing bill collectors that they did not open lines of credit accounts.

Because of the long-lasting value of PII, it sells for a much higher price on the black market — up to $15 per record. This is most often seen when companies storing a large volume of customer records experience a data breach, such as a healthcare insurer. This is much worse for susceptible consumers than a run-of-the-mill cardholder data breach, because of the threat of identity theft, which is more difficult to mitigate than credit card theft.

Company impact is also very high, but is still on par with a cardholder data breach in that a company experiences costs in response, credit monitoring, etc.; however, large-scale customer defection still has not been observed as a side effect. It’s important to note that government fines may be associated with this type of data breach, owing to the sensitive nature of the information.

Internal company information

This type of breach has often taken a backseat to the above-mentioned types, as it does not involve a customer’s personal details, but rather internal company information, such as emails, financial records, and intellectual property. The media focused on the Target and Home Depot hacks, for which the loss was considerable in terms of customer impact, but internal company leaks are perhaps the most damaging of all, as far as corporate impact.

The Sony Pictures Entertainment data breach eclipsed in magnitude anything that has occurred in the retail sector. SPE’s movie-going customers were not significantly impacted (unless you count having to wait a while longer to see ”The Interview” — reviews of the movie suggest the hackers did the public a favor); the damage was mostly internal. PII of employees was released, which could lead to identity theft, but the bulk of the damage occurred due to leaked emails and intellectual property. The emails themselves were embarrassing and clearly were never meant to see the light of day, but unreleased movies, scripts and budgets were also leaked and generously shared on the Internet.

Many firms emphasize data types that are regulated (e.g. cardholder data, health records, company financials) when measuring the impact of a data breach, but loss of intellectual property cannot be overlooked. Examine what could be considered “secret sauce” for different types of companies. An investment firm may have a stock portfolio for its clients that outperforms its competitors. A car company may have a unique design to improve fuel efficiency. A pharmaceutical company’s clinical trial results can break a company if disclosed prematurely.

Although it’s not thought of as a “firm” and not usually considered when discussing fissures in security, when the National Security Agency’s most secret files were leaked by flagrant whistleblower Edward Snowden, the U.S. government experienced a very significant data breach. Some would argue it is history’s worst of its kind, when considering the ongoing impact on the NSA’s secretive operations.

Now what?

Whenever I am asked to analyze a data breach or respond to a data breach, I am almost always asked, “How bad is it?” The short answer: it depends.

It depends on the type of data that was breached and how much of it. Many states do not require notification of a data breach of customer records unless it meets a certain threshold (usually 500). A company can suffer a massive system intrusion that affects the bottom line, but if the data is not regulated (e.g. HIPAA, GLBA) or doesn’t trigger a mandatory notification as required by law, the public probably won’t know about it.

Take a look at your firm’s data classification policy, incident response and risk assessments. A risk-based approach to the aforementioned is a given, but be sure you are including all data types and the wide range of threats and consequences.

Originally published at www.csoonline.com on March 17, 2015.