Risk modeling the vulnerability du jour, part 2: Forward-looking risk registers

Risk registers shouldn’t be a graveyard of past incidents—they should be living forecasts of future loss. Here’s how to model emerging threats like ShadowBrokers or Spectre and make your risk register proactive, not reactive.

"extreme horizon" by uair01 is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Strange, unusual, media-worthy vulnerabilities and cyberattacks… they seem to pop up every few months or so and send us risk managers into a fire drill. The inevitable questions follow: Can what happened to Yahoo happen to us? Are we at risk of a Heartbleed-type vuln? And, my personal favorite, Is this on our risk register?

This post is the second of a two-part series on how to frame, scope, and model unusual or emerging risks in your company's risk register. Part 1 covered how to identify, frame, and conceptualize these kinds of risks. Part 2, this post, introduces several tips and steps I use to brainstorm emerging risks and include the results in your risk register.

What’s a “forward-looking risk register”?

Before we get started, here’s the single most important takeaway of this blog post:

Risk registers should be forecasts, not a big ‘o list of problems that need to be fixed.

It shouldn't be a list of JIRA tickets of all the systems that are vulnerable to SQL injection, don't have working backups, or are policy violations. That's a different list.

A risk register:

Identifies the bad things that happen. For example, a threat uses SQL injection against your database and obtains your customer list

Forecasts the probability of the bad things happening, and

How much it could cost you if it does happen

In other words, risk registers look forward, not back. They are proactive, not reactive.

Including new threats and vector in your risk register

When I revamp a risk program, the first thing I do is make sure the company's risk register - the authoritative list of all risks that we know and care about - is as comprehensive and complete as possible. Next, I look for blind spots and new, emerging risks.

Here's my 4 step process to identify risk register blind spots, brainstorm new risks, how to integrate them into your register, and implement continuous monitoring.

Step 1: Inventory historical vulns and identify blind spots in your register

Run-of-the-mill risks like data breaches, outages, phishing, and fraud are easily turned into risk scenarios. It's a bit harder to identify risk blind spots. When a security incident story hits the major media and is big enough that I think I'm going to be asked about it, I start to analyze it. I look at who the threat actors are, their motivations, vector of attack, and probable impact. I then compare my analysis with the list of existing risks and ask myself, Am I missing anything? What lessons can I learn from the past to help me forecast the future?

Here are some examples:

| Vulnerability / Incident | What happened | Lessons for your risk register |

|---|---|---|

| Solarwinds hack (2020) | SolarWinds' software build process was infiltrated, giving attackers a foothold in Solarwinds customers' networks. | Software you trust gets delivered or updated with malware or provides access to system resources. |

| Target hack (2013) | Phishing email targeted at a vendor was successful, giving the attackers access to internal Target systems, leading to a breach of cardholder data. | Vendors you trust are compromised, giving attackers a foothold into your systems. |

| Sony Pictures Entertainment (SPE) (2014) | SPE released a movie that was unflattering to a particular regime, leading to a large-scale cyberattack that included ransom/extortion, massive data leaks, and a prolonged system outage. | State-sponsored groups or hacktivists are unhappy with a company's positions, products, leadership, or employee opinions and launch a cyber-attack in retaliation. |

| Rowhammer vuln | Privilege escalation and network-based attacks by causing a data leakage in DRAM. | There are hardware vulnerabilities that are OS-independent. OS/supplier diversification is not a panacea. |

| Spectre / Meltdown | An attacker exploits a vuln present in most modern CPUs, allowing access to data. | Same as above |

| Cold boot attack | An attacker with physical access to the target computer gains access to the data in memory. | You must assume that if an attacker is motivated, adequately resourced, and has the right knowledge, they can do anything with physical access to hardware. See the Evil Maid Attack. |

| Heartbleed | Bug in the OpenSSL library gives attackers access to data or the ability to impersonate sessions. | Linus’ Law (“given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow”) is not a risk mitigation technique. Open-source software has vulnerabilities just like commercial software, and sometimes they’re really bad. |

| Shadowbrokers leak (2016) | A massive leak of NSA hacking tools and zero-day exploits. | Criminal organizations and state-sponsored groups have some of the scariest tools and exploits and are unknown to software vendors and the general public. When these get leaked, adjust associated incident probabilities up. |

Step 2: Brainstorm any additional risks

"Brainstorms at INDEX: Views" by @boetter is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Keep it high-level and focus on resiliency instead of modeling out specific threat actions, methods, state-sponsored versus cybercriminals activity, etc. For example, you don't need to predict the next cold-boot type hardware attack. Focus on what you could do to improve overall security and resilience against scenarios in which the attackers have physical access to your hardware, whoever they may be.

Step 3: Integrate into the risk register

This step is a bit more complex, and the approach will significantly depend on your company's risk culture and what your audience expects out of a risk register.

One approach is to integrate your new scenarios into existing risk scenarios. For example, suppose you already have an existing data breach risk analysis. In that case, you can revisit the assumptions, probability of occurrence, and the factors that make up the loss side of the equation and ensure that events, such as Shadowbrokers or Target, are reflected.

Another approach is to create new risk scenarios, but this could make the register very busy with hypotheticals. Risk managers at Microsoft, the US State Department, and defense contractors probably would have a robust list of hypotheticals. The rest of us would just build the risks into existing scenarios.

Step 4: Continuous monitoring

As new attacks, methods, vectors, and vulnerabilities are made public, ask the following questions:

Conceptually and from a high level, do you have an existing scenario that covers this risk? Part 1 gives more advice on how to determine this.

Framing the event as a risk scenario, does it apply to your organization?

Is the risk plausible and probable, given your organization's risk profile? I never try to answer this myself; I convene a group of experts and elicit opinions.

In addition to the above, hold yearly emerging risk brainstorming sessions. What's missing, what's on the horizon, and where should we perform risk analyses?

I hope this gives you some good pointers to future-proof your risk register. What do you think? How do you approach identifying emerging risk? Let me know in the comments below.

Further reading

Risk modeling the vulnerability du jour, part 1: Framing

When the next headline-making exploit drops, your execs will ask, “Was this on our risk register?” This guide walks through how to proactively frame exotic or emerging threats—without falling into the FUD trap.

Every few months or so, we hear about a widespread vulnerability or cyber attack that makes its way to mainstream news. Some get snappy nicknames and their very own logos, like Meltdown, Specter, and Heartbleed. Others, like the Sony Pictures Entertainment, OPM, and Solarwinds attacks cause a flurry of activity across corporate America with executives asking their CISO’s and risk managers, “Are we vulnerable?”

I like to call these the vulnerability du jour, and I’m only half sarcastic when I say that. On the one hand, it’s a little annoying how sensationalized these are. Media-worthy vulnerabilities and attacks feel interchangeable: when one runs its course and attention spans drift, here’s another one to take its place, just like a restaurant’s soup of the day. On the other hand, if this is what it takes to get the boardroom talking about risk - I’ll take it.

When the vulnerability du jour comes on an executive’s radar, the third or fourth question is usually, “Was this on our risk register?” Of course, we don’t have crystal balls and can’t precisely predict the next big thing, but we can use brainstorming and thought exercises to ensure our risk registers are well-rounded. A well-rounded and proactive risk register includes as many of these events and vulnerabilities as possible - on a high level.

This is a two-part series, with this post (part 1) setting some basic guidelines on framing these types of risks. Part 2 gives brainstorming ideas on how to turn your risk register into one that’s forward-looking and proactive instead of reactive.

Building a forward-looking risk register means you’re holding at least annual emerging risk workshops in which you gather a cross-section of subject matter experts in your company and brainstorm any new or emerging risks to fill in gaps and blind spots in your risk register. I have three golden rules to keep in mind when you’re holding these workshops.

Golden Rules of Identifying Emerging Risk

#1: No specifics

Meteorologists, not Miss Cleo

We’re forecasters, not fortune tellers (think a meteorologist versus Miss Cleo). I don’t think anyone had “State-sponsored attackers compromise SolarWind’s source code build system, leading to a company data breach” in their list of risks before December 2020. (If you did - message me. I’d love to know if Elvis is alive and how he’s doing.)

Keep it high-level and focused on how the company can prepare for resiliency rather than a specific vector or method of attack. For example, one can incorporate the SolarWinds incident with a generalized risk statement like the example below. This covers the SolarWinds vector and other supply chain attacks and also provides a starting point to future-proof your risk register to similar attacks we will see in the future.

Attacker infiltrates and compromises a software vendor's source code and/or build and update process, leading to company security incidents (e.g. malware distribution, unauthorized data access, unauthorized system access.)The fallout from the incident can be further decomposed and quantified using FAIR’s 6 forms of loss or a similar model.

#2: Risk Quantification

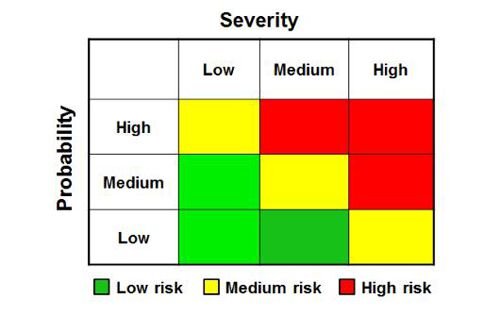

The risk matrix encourages FUD (fear, uncertainty, doubt)

Communicating hypothetical, speculative, or rare risks is hard to do without scaring people. If a good portion of your company’s risk register is stuff like hypervisor escapes, privilege escalation via rowhammer, and state-sponsored attacks you really need to have the data to back up why it needs executive attention. Otherwise, it will just look like another case of FUD.

The key to success is risk quantification: risk articulated in numbers, not colors. A bunch of red high risks (or green low risks) obfuscates the true story you are trying to tell.

All risk, because it’s forward-looking, is filled with uncertainty.

Unique and exotic risks have even more uncertainty. For example, there have been so many data breaches that we have a really good idea of how often they occur and how much it costs. Supply chain attacks like SolarWinds? Not so much. Choose a risk model that can communicate both the analyst’s uncertainty and the wide range of possibilities.

I use FAIR because it’s purpose-built for information and operational risks but you really can use any quantitative model.

#3: Be aware of risk blindness

Every good risk analyst knows the difference between risks that are possible and those that are probable. Without going too deep into philosophy, just about anything is possible and it’s the risk analyst’s job to reign in people when the risk brainstorming veers to outlandish scenarios. But, don’t reign them in too much!

Any risk, no matter how routine, was unique and a surprise to someone once upon a time. Ransomware would sound strange to someone in the 1970’s; computer crime would be received as black magic to someone in the 15th century.

Try to put yourself in this mindset as you hold emerging risk workshops. I personally love holding workshops with incident responders and red teamers - they have the ability to think outside of the box and are not shy about coming up with hypotheticals and highly speculative scenarios. Don’t discourage them. Yes, we still need to separate out possible from probable, but it is an emerging risk workshop. See what they come up with.

Next Up

I hope this post got you thinking about how to add these types of risks to your register. In part 2, I’m going to give real-life examples of how to further brainstorm and workshop out these risks.

Further reading

Black Swans and risk blindness

Black Swans aren't about rare events—they're about the risks we refuse to see. Here's how to spot your inner Thanksgiving turkey and avoid being blindsided by the next big shock.

I’ve noticed something unusual lately. There seems to be an increase in the number of events people are declaring Black Swans and the ensuing philosophic tug-of-war of detractors saying they’re wrong. At first, I thought people were just going for clickbait headlines, but I now feel something else is going on. We are experiencing a sort of collective risk blindness: we’re unable or unwilling to see emerging risk in front of us.

Keep in mind that the Black Swan is not a metaphor for sudden, surprise, high impact/low probability or catastrophic events. It’s a metaphor for risk blindness. Recall the parable of the Thanksgiving turkey:

Consider a turkey that is fed every day. Every single feeding will firm up the bird's belief that it is the general rule of life to be fed every day by friendly members of the human race 'looking out for its best interests,' as a politician would say. On the afternoon of the Wednesday before Thanksgiving, something unexpected will happen to the turkey. It will incur a revision of belief.”

- Nassim Taleb, “The Black Swan”

The Thanksgiving turkey is blind to risk. Cognitive bias, over-reliance on historical data, and not considering new, emerging risk led to it being surprised when it was served for dinner.

Both risk in general and Black Swans are observer-dependent. It’s in the eye of the beholder. 9/11 was a Black Swan to most of us, but not to John O’Neill. An accidental half-billion dollar wire transfer, Texas power outages, Gamestop stock volatility, and COVID-19 have all recently been declared Black Swans by some, but to others, the above examples were no surprise at all.

It’s no wonder that we’re starting to resemble Thanksgiving turkeys, unable to spot emerging risk. Risk blindness is why we are starting to see Black Swans everywhere. It seems tied to COVID-19 and all the recent political and social turmoil that’s happening. Every new big event seems surprising, and it shouldn’t be. Fighting cognitive bias, separating possible from probable, and looking beyond historical trends to see emerging threats takes work.

I’m tired. We’re all tired.

How do we ensure we’re not blind risk turkeys?

Recognize your built-in biases. Confirmation bias, anchoring, the availability effect, and overconfidence are present in every person. They cloud the decision-making process - especially when risk is involved. The corresponding Wikipedia article has a great list. Bias is an impediment to rational decision-making under uncertainty.

Diversification: Diversify your risk-seeking behavior. In other words, don’t put all your eggs in one basket.

Resiliency: Identify areas where you tend to be risk-averse and ensure you have resiliency. This could be extra liquidity, a plan B, some proactive measures, or just a recognition that you are overexposed in a particular area.

Think about how any of the above applies in your personal and professional life, weigh it against current events, what’s to come, and how you can take steps to reduce risk. For me, this is avoiding speculative investments, diversification, thinking about where I live and the risk that comes with it, thinking about insurance (do I have the right kind, in the right amounts), and ensuring that I have a plan B for critical decisions.

Footnote

I did a quick on-a-napkin brainstorming session of signficant 30-year risks that are top of mind. I’m thinking about each one and considering the following: a) how might my cognitive bias prevent me from seeing other risks? b) am I resilient to these risks, and c) if not, would diversification help me?

30 year Black Swan List (2021-2031)

(Risks that the collective “we” are blind to)

Cryptographic protocols go poof: A significant number of computer-based cryptographic protocols are unexpectedly and suddenly cracked or broken, leading to substantial financial, societal, and governmental repercussions. This could be from some kind of universal vulnerability, a monumental leap forward in computing power, artificial intelligence capabilities, or something else.

West Coast US Tsunami: Devastating tsunami on the US West Coast, most likely from an earthquake on the Cascadia subduction zone.

Extraterrestrial life is discovered: I don’t think microbe fossils on Mars would cause an adverse event, but if proof of extraterrestrial life is found to a degree that it causes large groups of people to question their religious views, there could be financial market shockwaves, panic selling, civic unrest, etc.

Another pandemic: COVID-19 scale pandemics are generally considered 100-year events, so another one in the next 30 years would shock many people. (Although those versed in probability theory know that another pandemic can happen today and still could be a 100-year event).

Twin pandemics: Speaking of pandemics, another one right now or two at the same time in the next 30 years is plausible.

Cryptocurrency is vaporized: Overnight (or very suddenly), the value of cryptocurrency (e.g. Bitcoin) plummets to near nothing. It could be from sudden government regulation, some kind of intentional devaluing, panic selling, the first event I listed (cryptographic protocols are broken), coordinated cyberattack/theft, or something else.

“Derecho” enters the popular lexicon: Devastating straight-line wind storms (as opposed to rotating - e.g. tornado, hurricane) become more frequent, extreme, damaging, and appear in places we’re not accustomed to seeing them. This is part of a trend of an increase in extreme weather globally.

Insurrection in the US: January 6, 2021 was just the beginning. Right-wing extremists perpetuate violent uprisings or terrorist attacks. Both the violence and subsequent law enforcement/military response cause financial, commerce, and civic repercussions.

The 2021 Security Outcomes report and better research methods

Most security surveys are junk science — biased, unrepresentative, and built to sell, not inform. Cisco’s 2021 report, in partnership with Cyentia, finally gets it right, showing the industry what statistically sound research actually looks like.

Something extraordinary happened recently in the Information Security research report area. Why I think it’s so extraordinary might have passed you by, unless you geek out on statistical methods in opinion polling as I do. The report is Cisco’s 2021 Security Outcomes report, produced in collaboration with the Cyentia Institute which is the only report in recent memory that uses sound, statistical methods in conducting survey-based opinion research. What is that and why is it so important? Glad you asked! <soapbox on>

The Current Problem

Numerous information security reports and research are survey-based, meaning they ask a group of people their opinion on something, aggregate the results, draw conclusions, then present the results. This is a very common -- and often illuminating -- way to perform research. It reveals the preferences and opinions of a group of people, which can further be used as a valuable input in an analysis. This method is called opinion polling, and we are all very familiar with this kind of research, mostly from political opinion polls that ask a group of people how they’re voting.

The single most important thing to keep in mind when evaluating the veracity of an opinion poll is knowing how respondents are selected.

If the people that comprise the group are selected at random, one can extrapolate the results to the general population.

If the people that comprise the group are not selected at random, the survey results only apply to the group itself.

Here’s the problem: most, if not all, survey-based information security reports make no effort to randomize the sample. As a consequence, the results are skewed. If a headline reads “40% of Ransomware Victims Pay Attackers” and the underlying research is non-random opinion polling, like a Twitter poll or emailing a customer list, the headline is misleading. The results only apply to the people that filled out the survey, not the general population. If you’re not following, let me use a more tangible example.

Let’s suppose you are a campaign worker for one of the candidates in the 2020 US Presidential campaign. You want to know who is ahead in California - Trump or Biden. The way you figure this out is to ask a group of people how they plan on voting on Election Day. I want to extrapolate the results to the whole of California - not just one area or demographic. It’s not feasible to ask every single Californian voter how they’re voting; just ask a representative sample. Which one of these polling methods do you think will yield the most accurate results?

Stand in front of a grocery store in Anaheim (the most conservative city in California) and ask 2000 people how they are voting

Stand in front of a grocery store in San Francisco (the most liberal city in California) and ask 2000 people how they are voting

Ask 2000 people on my Twitter account and offer them a $5 Amazon gift card to answer a poll on how they’re voting. It’s the honor system that they’re actually from California.

All three options will result in significant error and bias in the report, especially if the results are applied to how all Californians will vote. It’s called selection bias and it occurs when the group sampled is systematically different than the wider population being studied. Regardless if you work for the Biden or Trump campaign, you can’t use these survey results. Option 1 will skew toward Trump and option 2 will skew toward Biden - giving both teams an inaccurate view of how all Californians will vote. Option 3 would yield odd results, with people from all over the world completing the survey just to get the gift card.

Every survey-based security research report I’ve seen is conducted using non-randomized samples, like the examples above, and are subject to selection bias. If you’re a risk analyst like me, you can’t use reports like this - the results are just too questionable. I won’t use it. Junk research is the death of the defensibility of a risk assessment.

What Cyentia did

Let’s add a 4th option to the list above:

4. Obtain a list of all likely California voters, randomly sample enough people so that the likely response rate will be ~2000, and ask them how they plan on voting.

This method is much better; this gets us closer to a more accurate (or less wrong, following George Box’s aphorism) representation of how a larger group of people will vote.

Here’s the extraordinary thing: Cisco and Cyentia actually did it! They produced a research report based on opinion polling that adheres to sampling and statistical methods. They didn’t just ask 500 randos on Twitter with the lure of gift cards to answer a survey, like everyone else does. They went through the hard work to get a list, randomly sample it, debias the questions, and present the results in a transparent, usable way. This is the first time I’ve ever seen this in our industry and I truly hope it’s not the last.

A sea change?

Nearly all survey-based Information Security research reports cut corners, use poor methods, and typically use the results to scare and sell, rather than inform. The result is, at best, junk and at worst, actively harmful to your company if used to make decisions. I know that doing the right thing is hard and expensive, but it’s worth doing. Wade Baker of Cyentia wrote a blog post detailing the painstaking complexity of the sampling methodology. As a consumer of this research, I want Cyentia and Cisco to know that their hard work isn’t for nothing. The hard work means I and many others can use the results in a risk analysis.

I truly hope this represents a sea change in how security research is conducted. Thanks to everyone involved for going the extra mile - the results are remarkable.

Further Reading

Finally - a properly sampled security survey | blog post by Wade Baker on how the Cisco’s 2021 Security Outcomes report was designed

The good, the bad, and the ugly of public opinion polls | paper by Russell D. Renka

Sampling Methods Review by Khan Academy

Internet Surveys: Bad Data, Bad Science and Big Bias | blog post by Ian Chadwick

20 Questions A Journalist Should Ask About Poll Results | great post on opinion polling and ethics

Risk Mythbusters: We need actuarial tables to quantify cyber risk

Think you need actuarial tables to quantify cyber risk? You don’t — actuaries have been pricing rare, high-uncertainty risks for centuries using imperfect data, expert judgment, and common sense, and so can you.

Risk management pioneers: The New Lloyd's Coffee House, Pope's Head Alley, London

The auditor stared blankly at me, waiting for me to finish speaking. Sensing a pause, he declared, “Well, actually, it’s not possible to quantify cyber risk. You don’t have cyber actuarial tables.” If I had a dollar for every time I heard that… you know how the rest goes.

There are many myths about cyber risk quantification that have become so common, they border on urban legend. The idea that we need vast and near-perfect historical data is a compelling and persistent argument, enough to discourage all the but the most determined of risk analysts. Here’s the flaw in that argument: actuarial science is a varied and vast discipline, selling insurance on everything from automobile accidents to alien abduction - many of which do not have actuarial tables or even historical data. Waiting for “perfect” historical data is a fruitless exercise and will prevent the analyst from using the data at hand, no matter how sparse or flawed, to drive better decisions.

Insurance without actuarial tables

Many contemporary insurance products, such as car, house, fire, and life have rich historical data today. However, many insurance products have for decades - in some cases, centuries - been issued without historical data, actuarial tables, or even good information. For those still incredulous, consider the following examples:

Auto insurance: Issuing auto insurance was unheard of when the first policy was issued in 1898. Companies only insured horse-drawn carriages up to that point, and actuaries used data from other types of insurance to set a price.

Celebrities’ body parts: Policies on Keith Richards’ hands and David Beckham’s legs are excellent tabloid fodder, but also a great example of how actuaries are able to price rare events.

First few years of cyber insurance: Claims data was sparse in the 1970’s, when this product was first conceived, but there was money to be made. Insurance companies set initial prices based on estimates and adjacent data. Prices were adjusted as claims data became available.

There are many more examples: bioterrorism, capital models, and reputation insurance to name a few.

How do actuaries do it?

Many professions, from cyber risk to oil and gas exploration, use the same estimation methods developed by actuaries hundreds of years ago. Find as much relevant historical data as possible - this can be adjacent data, such as the number of horse-drawn carriage crashes when setting a price for the first automobile policy - and bring it to the experts. Experts then apply reasoning, judgment, and their own experience to set insurance prices or estimate the probability of a data breach.

Subjective data encoded quantitatively isn’t bad! On the contrary, it’s very useful when there is deep uncertainty, sparse data, data is expensive to acquire or a new, emerging risk.

I’m always a little surprised when people reject better methods altogether, citing the lack of “perfect data,” then swing in the opposite direction to gut checks and wet finger estimation. The tools and techniques are out there to make cyber risk quantification not only possible but could give any company a competitive edge. Entire industries have been built around less than perfect data and we as cyber risk professionals should not use a lack of perfect data as an excuse not to quantify cyber risk. If there is a value placed on Tom Jones' chest hair then certainly we can predict the loss risk of a data incident... go ask the actuaries!

Better Security Metrics with Biff Tannen

Can your metrics pass the Biff Test? If a time-traveling dimwit like Back to the Future's Biff Tannen can fetch and understand your metric, it’s probably clear enough to guide better decisions.

In a previous post, I wrote about testing metrics with The Clairvoyant Test. In short, a metric is properly written if a clairvoyant, who only has the power of observation, can identify it.

Some people struggle with The Clairvoyant Test. They have a hard time grasping the rules: the clairvoyant can observe anything but cannot make judgments, read minds or extrapolate. It’s no wonder they have a hard time; our cultural view of clairvoyants is shaped by the fake ones we see on TV. For example, Miss Cleo, John Edward, and Tyler “The Hollywood Medium” Henry often do make personal judgments and express opinions about future events. Almost every clairvoyant we see in movies and TV can read minds. I think people get stuck on this, and often will declare metrics or measurements as incorrectly passing The Clairvoyant Test due to the cultural perception that clairvoyants know everything.

Since this is a cultural problem and not a technical one, is there a better metaphor we can use? Please allow me to introduce you to Biff Tannen.

Meet Biff

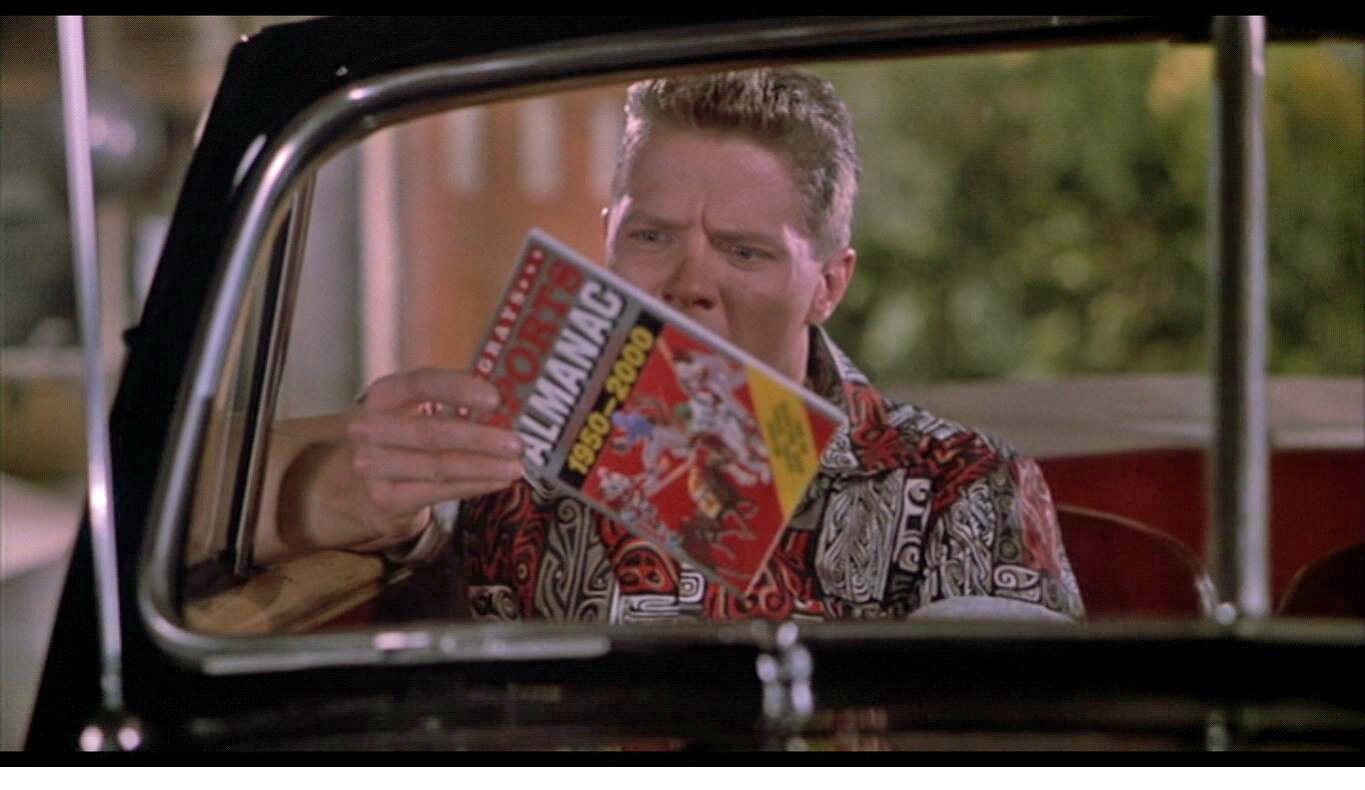

Biff Tannen is the main villain in all three Back to the Future movies. In Back to the Future II, Biff steals Doc’s time-traveling DeLorean in 2015 for nefarious reasons. Among other shenanigans, 2015 Biff gives a sports almanac to 1955 Biff, providing the means for him to become a multi-millionaire and ruining Hill Valley in the process.

If you recall, Biff has the following negative characteristics:

He’s a dullard and has no conjecture abilities

He lacks common sense

He has little judgment or decision-making capabilities

He’s a villain, so you can’t trust him

But...

He has access to Doc’s time-traveling DeLorean so he can go to any point in the future and fetch, count, look up or directly observe something for you.

Here’s how Biff Tannen can help you write better metrics: if Biff can understand and fetch the value using his time-traveling DeLorean, it’s a well-written metric. Metrics have to be clear, unambiguous, directly observable, quantifiable, and not open to interpretation.

You should only design metrics that are Biff-proof. Biff gets stuck on ambiguity, abstractions and can only understand concepts that are right in front of him, such as the sports almanac. He can only count through observation due to low intelligence and lacks judgment and common sense. If you design a metric that Biff Tannen can fetch for you, it will be understood and interpreted by your audience. That’s the magic in this.

How to Use the Biff Test: A Few Examples

Metric: % of vendors with adequate information security policies

Biff cannot fetch this metric for you; he has no judgment or common sense. He will get stuck on the word “adequate” and not know what to do. Your audience, reading the same metric, will also get confused and this opens the measurement up to different interpretations. Let’s rewrite:

New Metric: % of vendors with information security policies in compliance with the Company’s Vendor Security Policy

The re-written metric assumes there is a Vendor Security Policy that describes requirements. The new metric is unambiguous and clear. Biff – with his limited abilities – can fetch it.

Metric: % of customer disruption due to downtime

This one is slightly more complex but perhaps seen on many lists of company metrics. Biff would not be able to fetch this metric for us. “Disruption” is ambiguous, and furthermore, think about the word“downtime.” Downtime of what? How does that affect customers? Let’s re-write this into a series of metrics that show the total picture when shown as a set.

New Metrics:

Total uptime % on customer-facing systems

% customer-facing systems meeting uptime SLAs

Mean-time to repair (RTTR) on customer-facing systems

# of abandoned customer shopping carts within 24 hours following an outage

Biff can fetch the new metric and non-IT people (your internal customers!) will be able to interpret and understand them.

Metric: % of critical assets that have risk assessments performed at regular intervals

Biff doesn’t have judgment and gets confused at “regular intervals.” He wonders, what do they mean by that? Could “regular” mean once a week or every 10 years?

New Metric: % of critical assets that have risk assessments performed at least quarterly

The rewritten metric assumes that “critical asset” and “risk assessment” have formal definitions in policies. If so, one small tweak and now it passes the Biff Test.

Conclusion and Further Work

Try this technique with the next security metric you write and anything else you are trying to measure, such as OKR’s, performance targets, KRIs and KPIs.

I often ask a lay reader to review my writing to make sure it's not overly technical and will resonate with broad audiences. For this same reason, we would ask Biff - an impartial observer with a time machine - to fetch metrics for us.

Of course, I’m not saying your metric consumers are as dull or immoral as Biff Tannen, but the metaphor does make a good proxy for the wide range of skills, experience, and backgrounds that you will find in your company. A good metric that passes the test means that it’s clear, easy to understand and will be interpreted the same way by the vast majority of people. Whether you use the Biff or the Clairvoyant Test, these simple thought exercises will help you write crisp and clear metrics.

Better Security Metrics with the Clairvoyant Test

Think your security metrics are clear? Put them to the test—The Clairvoyant Test—a thought experiment that strips away ambiguity, subjectivity, and fuzziness to make sure your metrics are measurable, observable, and decision-ready.

"Clairvoyant at Whitby" by Snapshooter46 is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

There’s an apocryphal business quote from Drucker, Demmings, or maybe even Lord Kelvin that goes something like this: “You can’t manage what you don’t measure.” I’ll add that you can’t measure what you don’t clearly define.

Clearly defining the object of measurement is where many security metrics fail. I’ve found one small trick borrowed from the field of Decision Science that helps in the creation and validation of clear, unambiguous, and succinct metrics. It’s called The Clairvoyant Test, and it’s a 30-second thought exercise that makes the whole process quick and easy.

What is the Clairvoyant Test?

The Clairvoyant Test was first introduced in 1975 as a decision analysis tool in a paper titled “Probability Encoding in Decision Analysis” by Spetzler and Von Holstein. It’s intended to be a quick critical thinking tool to help form questions that ensure what we want to measure is, in reality, measurable. It’s easily extended to security metrics by taking the metric description or definition and passing it through the test.

The Clairvoyant Test supposes that one can ask a clairvoyant to gather the metric, and if they are able to fetch it, it is properly formed and defined. In real life, the clairvoyant represents the uninformed observer in your company.

There’s a catch, and this is important to remember: the clairvoyant only has the power of observation.

The Catch: Qualities of the Clairvoyant

The clairvoyant can only view events objectively through a crystal ball (or whatever it is clairvoyants use).

They cannot read minds. The clairvoyant’s powers are limited to what can be observed through the crystal ball. You can’t ask the clairvoyant if someone is happy, if training made them smarter, or if they are less likely to reuse passwords over multiple websites.

The clairvoyant cannot make judgments. For example, you can’t ask if something is good, bad, effective, or inefficient.

They can only observe. Questions posed to the clairvoyant must be framed as observables. If your object of measurement can’t be directly observed, decompose the problem until it can be.

They cannot extrapolate. The clairvoyant cannot interpret what you may or not mean, offer conjecture or fill in the gaps of missing information. In other words, they can only give you data.

What’s a well-designed metric that passes the Clairvoyant Test?

A well-designed metric has the following attributes:

Unambiguous: The metric is clearly and concisely written; in fact, it is so clear and so concise that there is very little room for interpretation. For example, the number of red cars on Embarcadero St. between 4:45 and 5:45 pm will be interpreted the same way by the vast majority of people.

Objective: Metrics avoid subjective judgments, such as “effective” or “significant.” Those words mean different things to different people and can vary greatly across age, experience, cultural, and language backgrounds.

Quantitative: Metrics need to be quantitative measurements. “Rapid deployment of critical security patches” is not quantitative; “Percentage of vulnerabilities with an EPSS probability of 80% of higher remediated within ten days” is.

Observable: The metrics need to be designed so that anyone, with the right domain knowledge and access, can directly observe the event you are measuring.

A few examples…

Let’s try a few common metrics and pass through The Clairvoyant Test to see if they’re measurable and written concisely.

Metric: % of users with privileged access

The clairvoyant would not be able to reveal the value of the metric. “Privileged access” is a judgment call and means different things to different people. The clairvoyant would also need to know what system to look into. Let’s rewrite:

New Metric: % of users with Domain Admin on the production Active Directory domain

The new metric is objective, clear, and measurable. Additional systems and metrics (root on Linux systems, AWS permissions, etc.) can be aggregated.

Let’s try a metric that is a little harder:

Metric: Percentage of vendors with effective cybersecurity policies.

The clairvoyant would not be able to reveal this either – “effective” is subjective, and believe it or not – a cybersecurity policy is not the same across all organizations. Some have a 50-page documented program, others have a 2-page policy, and even others would provide a collection of documents: org chart, related policies, and a 3-year roadmap. Rewritten, “effective” needs to be defined, and “policy” needs to be decomposed. For example, a US-based bank could start with this:

New Metric: % of vendors that have a written and approved cybersecurity policy that adheres to FFIEC guidelines.

This metric is a good starting point but needs further work – the FFIEC guidelines by themselves don’t pass The Clairvoyant Test, but we’re getting closer to something that does. We can now create an internal evaluation system or scorecard for reviewing vendor security policies. In this example, keep decomposing the problem and defining attributes until it passes The Clairvoyant Test.

Conclusion and Further Work

Do your security metrics pass The Clairvoyant Test? If they don’t, you may have a level of ambiguity that leads to audience misinterpretation. Start with a few metrics and try rewriting them. You will find that clearly stated and defined metrics leads to a security program that is easier to manage.

Probability & the words we use: why it matters

When someone says there's a "high risk of breach," what do they really mean? This piece explores how fuzzy language sabotages decision-making—and how risk analysts can replace hand-wavy terms with probabilities that actually mean something.

The medieval game of Hazard

So difficult it is to show the various meanings and imperfections of words when we have nothing else but words to do it with. -John Locke

A well-studied phenomenon is that perceptions of probability vary greatly between people. You and I perceive the statement “high risk of an earthquake” quite differently. There are so many factors that influence this disconnect: one’s risk tolerance, events that happened earlier that day, cultural and language considerations, background, education, and much more. Words sometimes mean a lot, and other times, convey nothing at all. This is the struggle of any risk analyst when they communicate probabilities, forecasts, or analysis results.

Differences in perception can significantly impact decision making. Some groups of people have overcome this and think and communicate probabilistically - meteorologists and bookies come to mind, but other areas such as business, lag far behind. My position has always been that if business leaders can start to think probabilistically, like bookies, significantly better risk decisions can be made, yielding an advantage over their competitors. I know from experience, however, that I need to first convince you there’s a problem.

The Roulette Wheel

A pre-COVID trip to Vegas reminded me of the simplicity in betting games and their usefulness in explaining probabilities. Early probability theory was developed to win at dice games, like hazard - a precursor to craps - not to advance the field of math.

Imagine this scenario: we walk into a Las Vegas casino together and I place $2,000 on black on the roulette wheel. I ask you, “What are my chances of winning?” How would you respond? It may be one of the following:

You have a good chance of winning

You are not likely to win

That’s a very risky bet, but it could go either way

Your probability of winning is 47.4%

Which answer above is most useful when placing a bet? The last one, right? But, which answer is the one you are most likely to hear? Maybe one of the first three?

All of the above could be typical answers to such a question, but the first three reflect attitudes and personal risk tolerance, while the last answer is a numerical representation of probability. The last one is the only one that should be used for decision making; however, the first three examples are how humans talk.

I don’t want us all walking around like C3PO, quoting precise odds of successfully navigating an asteroid field at every turn, but consider this: not only is “a good chance of winning” not helpful, you and I probably have a different idea of what “good chance” means!

The Board Meeting

Let’s move from Vegas to our quarterly Board meeting. I've been in many situations where metaphors are used to describe probabilities and then used to make critical business decisions. A few recent examples that come to mind:

We'll probably miss our sales target this quarter.

There's a snowball's chance in hell COVID infection rates will drop.

There's a high likelihood of a data breach on the customer database.

Descriptors like the ones above are the de facto language of forecasting in business: they're easy to communicate, simple to understand, and do not require a grasp of probability - which most people struggle with. There's a problem, however. Research shows that our perceptions of probability vary widely from person to person. Perceptions of "very likely" events are influenced by many factors, such as gender, age, cultural background, and experience. Perceptions are further influenced by the time of day the person is asked to make the judgment, a number you might have heard recently that the mind anchors to, or confirmation bias (a tendency to pick evidence that confirms our own beliefs).

In short, when you report “There's a high likelihood of a data breach on the customer database” each Board member interprets “high likelihood” in their own way and makes decisions based on the conclusion. Any consensus about how and when to respond is an illusion. People think they’re on the same page, but they are not. The CIA and the DoD noticed this problem in the 1960’s and 1970’s and set out to study it.

The CIA’s problem

One of the first papers to tackle this work is a 1964 CIA paper, Words of Estimative Probability by Sherman Kent. It's now declassified and a fascinating read. Kent takes the reader through how problems arise in military intelligence when ambiguous phrases are used to communicate future events. For example, Kent describes a briefing from an aerial reconnaissance mission.

Aerial reconnaissance of an airfield

Analysts stated:

"It is almost certainly a military airfield."

"The terrain is such that the [redacted] could easily lengthen the runways, otherwise improve the facilities, and incorporate this field into their system of strategic staging bases. It is possible that they will."

"It would be logical for them to do this and sooner or later they probably will."

Kent describes how difficult it is to interpret these statements meaningfully; not to mention, make strategic military decisions.

The next significant body of work on this subject is "Handbook for Decision Analysis" by Scott Barclay et al for the Department of Defense. A now-famous 1977 study was conducted on 23 NATO officers, asking them to match probabilities, articulated in percentages, to probability statements. The officers were given a series of 16 statements, including:

It is highly likely that the Soviets will invade Czechoslovakia.

It is almost certain that the Soviets will invade Czechoslovakia.

We believe that the Soviets will invade Czechoslovakia.

We doubt that the Soviets will invade Czechoslovakia.

Only the probabilistic words in bold (emphasis added) were changed across the 16 statements. The results may be surprising:

"Handbook for Decisions Analysis" by Scott Barclay et al for the Department of Defense, 1977

It is obvious that the officers' perceptions of probabilities are all over the place. For example, there's an overlap with "we doubt" and "probably," and the inconsistencies don't stop there. The most remarkable thing is that this phenomenon isn't limited to 23 NATO officers - take any group of people, ask them the same questions, and you will see very similar results.

Can you imagine trying to plan for the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, literal life and death decisions, and having this issue? Let’s suppose intelligence states there's a “very good chance” of an invasion occurring. One officer thinks “very good chance” feels about 50/50 - a coin flip. Another thinks that’s a 90% chance. They both nod in agreement and continue war planning!

Can I duplicate the experiment?

I recently discovered a massive, crowdsourced version of the NATO officer survey called www.probabilitysurvey.com. The website collects perceptions of probabilistic statements, then shows an aggregated view of all responses. I took the survey to see if I agreed with the majority of participants, or if I was way off base.

My perceptions of probabilities (from www.probabilitysurvey.com). The thick black bars are my answers

I was surprised that some of my responses were so different than others, yet others were in line with everyone else. I work with probabilities every day and work with people to translate what they think is possible, and probable, to probabilistic statements. Thinking back, I consider many terms in the survey as synonymous with each other, while others perceive slight variations.

This is even more proof that if you and I are in a meeting, talking about high likelihood events, we will have different notions of what that means, leading to mismatched expectations and inconsistent outcomes. This can destroy the integrity of a risk analysis.

What can we do?

We can't really "fix" this, per se. It's a condition, not a problem. It's like saying, "We need to fix the problem that everyone has a different idea of what 'driving fast' means." We need to recognize that perceptions vary among people and adjust our own expectations accordingly. As risk analysts, we need to be intellectually honest when we present risk forecasts to business leaders. When we walk into a room and say “ransomware is a high likelihood event,” we know that every single person in the room hears “high” differently. One may think it’s right around the corner and someone else may that’s a once-every-ten-years event and have plenty of time to mitigate.

That’s the first step. Honesty.

Next, start thinking like a bookie. Experiment with using mathematical probabilities to communicate future events in any decision, risk, or forecast. Get to know people and their backgrounds; try out different techniques with different people. For example, someone who took meteorology classes in college might prefer probabilities and someone well-versed in gambling might prefer odds. Factor Analysis of Information Risk (FAIR), an information risk framework, uses frequencies because it’s nearly universally understood.

For example,

"There's a low likelihood of our project running over budget."

Becomes…

There's a 10% chance of our project running over budget.

Projects like this one, in the long run, will run over budget about once every 10 years.

Take the quiz yourself on www.probabilitysurvey.com. Pass it around the office and compare results. Keep in mind there is no right answer; everyone perceives probabilistic language differently. If people are sufficiently surprised, test out using numbers instead of words.

Numbers are unambiguous and lead to clear objectives, with measurable results. Numbers need to become the new de facto language of probabilities in business. Companies that are able to forecast and assess risk using numbers instead of soft, qualitative adjectives, will have a true competitive advantage.

Resources

Words of Estimative Probability by Sherman Kent

Handbook for Decisions Analysis by Scott Barclay et al for the Department of Defense

Take your own probability survey

Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman | a deep exploration into this area and much, much more

Recipe for passing the OpenFAIR exam

Thinking about the OpenFAIR certification? Here's a practical, no-fluff study guide to help you prep smarter—not harder—and walk into the exam with confidence.

Passing and obtaining the OpenGroup’s OpenFAIR certification is a big career booster for information risk analysts. Not only does it look good on your CV, it demonstrates your mastery of FAIR to current and potential employers. It also makes a better analyst because it deepens one’s understanding of risk concepts that may not be often used. I passed the exam myself a while back, and I’ve also helped people prepare and study for it. This is my recipe for studying for and passing the OpenFAIR exam.

What to study

The first thing you need to understand in order to pass the exam is that the certification is based on the published OpenFAIR standard, last updated in 2013. Many people and organizations - bloggers, risk folks on Twitter, the FAIR Institute, me, Jack Jones himself - have put their own spin and interpretation on FAIR in the years since the standard was published. Reading this material is important to becoming a good risk analyst but it won’t help you pass the exam. You need to study and commit to memory the OpenFAIR standard. If you find contradictions in later texts, favor the OpenFAIR documentation.

Now, get your materials

The two most important texts are:

Open Risk Taxonomy Technical Standard (O-RT) - free, registration required

Open Risk Analysis Technical Standard (O-RA) - free, registration required

Two more optional texts, but highly recommended:

OpenFAIR Foundation Study Guide - $29.95

Measuring and Managing Information Risk: A FAIR Approach by Jack Freund and Jack Jones - book, $49.95 on Amazon

How to Study

This is how I recommend you study for the exam:

Thoroughly read the Taxonomy (O-RT) and Analysis (O-RA) standards, cover to cover. Use the FAIR book, blogs, and other papers you find to help answer questions or supplement your understanding, but use the PDF’s as your main study aid.

Start memorizing - there are only three primary items that require rote memorization; everything else is common sense if you have a mastery of the materials. Those items are:

The Risk Management Stack

You need to know what they are, but more importantly, you need to know them in order.

Accurate models lead to meaningful measurements, which lead to effective comparisons - you get the idea. The test will have several questions like, “What enables well-informed decisions?” Answer: effective comparisons. I never did find a useful mnemonic that stuck like Please Don’t Throw Sausage Pizzas Away, but try to come up with something that works for you.

The FAIR Model

You are probably already familiar with the FAIR model and how it works by now, but you need to memorize it exactly as it appears on the ontology.

The FAIR model (source: FAIR Institute)

It’s not enough to know that Loss Event Frequency is derived from Threat Event Frequency and Vulnerability - you need to know that Threat Event Frequency is in the left box and Vulnerability is on the right. Once a day, draw out 13 blank boxes and fill them in. The test will ask you to match various FAIR elements of risk on an empty ontology. You also need to know if each element is a percentage or a number. This should be easier to memorize if you have a true understanding of the definitions.

Forms of Loss

Last, you need to know the six forms of loss. You don’t need to memorize the order, but you definitely need to recognize these as the six forms of loss and have a firm understanding of the definitions.

Productivity Loss

Response Loss

Replacement Loss

Fines and Judgements

Competitive Advantage

Reputation Damage

Quiz Yourself

I really recommend paying the $29.95 for the OpenFAIR Foundation Study Guide PDF. It has material review, questions/answers at the end of each chapter, and several full practice tests. The practice tests are so similar (even the same, for many questions) to the real test, that if you ace the practice tests, you’re ready. Also, check out FAIR certification flashcards for help in understanding the core concepts.

When you think you’re ready, register for your exam for a couple of weeks out. This gives you time to keep taking practice tests and memorizing terms.

In Closing…

It’s not a terribly difficult test, but you truly need a mastery of the FAIR risk concepts to pass. I think if you have a solid foundation in risk analysis in general, it takes a few weeks to study, as opposed to months for the CRISC or CISSP.

Good luck with your FAIR journey! As always, feel free to reach out to me or ask questions in the comments below.

No, COVID-19 is not a Black Swan event*

COVID-19 isn’t a Black Swan—it was predicted, modeled, and even planned for. So why are so many leaders acting like turkeys on Thanksgiving?

*Unless you’re a turkey

It’s really a White Ostrich event

There’s a special kind of history re-writing going on right now among some financial analysts, risk managers, C-level leadership, politicians and anyone else responsible for forecasting and preparing for major business, societal and economic disruptions. We’re about 3 months into the COVID-19 outbreak and people are starting to declare this a “Black Swan” event. Not only is “Black Swan” a generally bad and misused metaphor, the current pandemic also doesn’t fit the definition. I think it’s a case of CYA.

Just a few of many examples:

Marketwatch quoted an advisory firm founder stating the stock market fall is a “black swan market drop.”

The Nation predicted on February 25, 2020 that “The Coronavirus Could Be the Black Swan of 2020.”

Forbes declared on March 19, 2020: COVID-19 is a Black Swan.

My LinkedIn and Twitter feed is filled with Black Swan declarations or predictions that the coming economic ramifications will be Black Swan events.

None of this is a Black Swan event. COVID-19, medical supply shortages, economic disaster – none of it.

Breaking Black Swans down

The term “Black Swan” became part of the business lexicon in 2007 with Nassim Taleb’s book titled The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. In it, Taleb describes a special kind of extreme, outlier event that comes as a complete surprise to the observer. The observer is so caught off-guard that rationalization starts to occur: they should have seen it all along.

According to Taleb, a Black Swan event has these three attributes:

“First, it is an outlier, as it lies outside the realm of regular expectations, because nothing in the past can convincingly point to its possibility. Second, it carries an extreme ‘impact’. Third, in spite of its outlier status, human nature makes us concoct explanations for its occurrence after the fact, making it explainable and predictable.”

Let’s take the Black Swan definition and fit it to everything that’s going on now.

“First, it is an outlier, as it lies outside the realm of regular expectations, because nothing in the past can convincingly point to its possibility.”

COVID-19 and all of the fallout, deaths, the looming humanitarian crisis, economic disaster and everything in-between is the opposite of what Taleb described. In risk analysis, we use past incidents to help inform forecasting of future events. We know a lot about past pandemics, how they happen and what occurs when they do. We’ve had warnings and analysis that the world is unprepared for a global pandemic. What is looming should also be of no surprise: past pandemics often significantly alter economies. A 2019 pandemic loss assessment by the World Health Organization (WHO) feels very familiar as well as many recent threat assessments that show this was expected in the near-term future. Most medium and large companies have pandemic planning and response as part of their business continuity programs. In other words, past is prologue. Everything in the past convincingly points to the possibility of a global pandemic.

Perhaps the details of COVID-19’s origins may be a surprise to some, but the relevant information needed for risk managers, business leaders and politicians to become resilient and prepare for these events should be of absolutely no surprise. It’s true that when is not knowable, but that’s is the purpose of risk analysis. We don’t ignore high impact, low probability events.

“Second, it carries an extreme ‘impact’.”

This might be the only aspect of what we’re currently experiencing that fits the Black Swan definition, but extreme impact alone does not make the COVID-19 pandemic a Black Swan. The COVID-19 impact today is self-evident, and what’s to come is foreseeable.

“Third, in spite of its outlier status, human nature makes us concoct explanations for its occurrence after the fact, making it explainable and predictable.”

When a true Black Swan occurs, according to Taleb, observers start rationalizing: oh, we should have predicted it, signs were there all along, etc. Think about what this means – before the Black Swan event it’s unfathomable; after, it seems completely reasonable.

We are seeing the exact opposite now. The select folks who are outright calling this a Black Swan aren’t rationalizing that it should have or could have been predicted; they are now saying it was completely unpredictable. From POTUS saying the pandemic “snuck up on us,” to slow response from business, there’s some revisionist thinking going on.

I’m not sure why people are calling this a Black Swan. I suspect it’s a combination of misunderstanding what a Black Swan is, politicians playing CYA and fund managers trying to explain to their customers why their portfolios have lost so much value.

It’s a Black Swan to turkeys

“Uncertainty is a feature of the universe. Risk is in the eye of the beholder.”

-Sam Savage

Taleb explains in his book that Black Swans are observer-dependent. To explain this point, he tells the story of the Thanksgiving turkey in his book.

“Consider a turkey that is fed every day. Every single feeding will firm up the bird's belief that it is the general rule of life to be fed every day by friendly members of the human race 'looking out for its best interests,' as a politician would say. On the afternoon of the Wednesday before Thanksgiving, something unexpected will happen to the turkey. It will incur a revision of belief.”

For the turkey, Thanksgiving is a Black Swan event. For the cook, it certainly is not. It’s possible that some are truly turkey politicians, risk managers and business executives in this global pandemic. However, I don’t think there are many. I think most happen to be a different kind of bird.

If the COVID-19 pandemic isn’t a Black Swan…

If the COVID-19 pandemic isn’t a Black Swan event, what is it? My friend and fellow risk analyst Jack Whitsitt coined phrase White Ostrich and had this to say:

I like Taleb’s book. It’s a fascinating read on risk and risk philosophy, but the whole Black Swan metaphor is misused, overused and doesn’t make much sense outside the parameters that he sets. I’ve written about the bad metaphor problem the context of cyber risk. I also recommend reading Russell Thomas’s blog post on different colored swans. It will illuminate the issues and problems we face today.

Book Review | The Failure of Risk Management: Why It's Broken and How to Fix It, 2nd Edition

Doug Hubbard’s The Failure of Risk Management ruffled feathers in 2012—and the second edition lands just as hard, now with more tools, stories, and real-world tactics. If you’ve ever been frustrated by heat maps, this book is your upgrade path to real, defensible risk analysis.

When the first edition of The Failure of Risk Management: Why It's Broken and How to Fix It by Douglas Hubbard came out in 2012, it made a lot of people uncomfortable. Hubbard laid out well-researched arguments that some of businesses’ most popular methods of measuring risk have failed, and in many cases, are worse than doing nothing. Some of these methods include the risk matrix, heat map, ordinal scales, and other methods that fit into the qualitative risk category. Readers of the 1st edition will know that the fix is, of course, methods based on mathematical models, simulations, data, and evidence collection. The 2nd edition, released in March 2020, builds on the work of the previous edition but brings it into 2020 with more contemporary examples of the failure of qualitative methods and tangible advice on how to incorporate quantitative methods into readers’ risk programs. If you considered the 1st edition required reading, as many people do (including myself), the 2nd edition is a worthy addition to your bookshelf because of the extra content.

The closest I’ll get to an unboxing video

The book that (almost) started it all

I don’t think it would be fair to Jacob Bernoulli’s 1713 book Ars Conjectandi to say that the first edition of The Failure of Risk Management started it all, but Hubbard’s book certainly brought concepts such as probability theory into the modern business setting. Quantitative methodologies have been around for hundreds of years, but in the 1980’s and ‘90’s people started to look for shortcuts around the math, evidence gathering, and critical thinking. Those companies starting using qualitative models (e.g., red/yellow/green, high/medium/low, heat maps) and these, unfortunately, became the de facto language of risk in most business analysis. Hubbard noticed this and carefully laid out an argument on why these methods are flawed and gave readers tangible examples of how to re-integrate quantitative methodologies into decision and risk analysis.

Hubbard eloquently reminds readers in Part Two of his new book all the reasons why qualitative methodologies have failed us. Most readers should be familiar with the arguments at this point and will find the “How to Fix It” portion of the book, Part Three, a much more interesting and compelling read. We can tell people all day how they’re using broken models, but if we don’t offer an alternative they can use, I fear arguments will fall on deaf ears. I can't tell you how many times I've seen a LinkedIn risk argument (yes, we have those) end with, “Well, you should have learned that in Statistics 101.” We’ll never change the world this way.

Hubbard avoids the dogmatic elements of these arguments and gives all readers actionable ways to integrate data-based decision making into risk programs. Some of the topics he covers include calibration, sampling methods for gathering data, an introduction to Monte Carlo simulations, and integrating better risk analysis methods into a broader risk management program. What's most remarkable isn't what he covers, but how he covers it. It’s accessible, (mostly) mathless, uses common terminology, and is loaded with stories and anecdotes. Most importantly, the reader can run quantitative risk analysis with Monte Carlo simulations from the comfort on their own computer with nothing more than Excel. I know that Hubbard has received criticism for using Excel instead of more typical data analysis software, such as Python or R, but I see this as a positive. With over 1.2 billion installs of Excel worldwide, readers can get started today instead of learning how to code and struggling with installing new software and packages. Anyone with motivation and a computer can perform quantitative risk analysis.

What’s New?

There are about 100 new pages in the second edition, with most being new content, but some readers will recognize concepts from Hubbard’s newer books, like the 2nd edition of How to Measure Anything and How to Measure Anything in Cybersecurity Risk. Some of the updated content includes:

An enhanced introduction, that includes commentary on the many of the failures of risk management that has occurred since the 1st edition was published, such as increased cyber-attacks and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

I was delighted to see much more content around how to get started in quantitative modeling in Part 1. Readers only need a desire to learn, and not a ton of risk or math experience to get started immediately.

Much more information is provided on calibration and how to reduce cognitive biases, such as the overconfidence effect.

Hubbard beefed up many sections with stories and examples, helping the reader connect even the most esoteric risk and math concepts to the real world.

Are things getting better?

It’s easy to think that things haven’t changed much. After all, most companies, frameworks, standards, and auditors still use qualitative methodologies and models. However, going back and leafing through the 1st edition and comparing it with the 2nd edition made me realize there has been significant movement in the last eight years. I work primarily in the cyber risk field, so I'm only going to speak to that subject, but the growing popularity of Factor Analysis of Information Risk (FAIR) – a quantitative cyber risk model – is proof that we are moving away from qualitative methods, albeit slowly. There are also two national conferences, FAIRcon and SIRAcon, that are dedicated to advancing quantitative cyber risk practices – both of which didn’t exist in 2012.

I'm happy that I picked up the second edition. The new content and commentary are certainly worth the money. If you haven’t read either edition and want to break into the risk field, I would add this to your required reading list and make sure you get the newer edition. The book truly changed the field for the better in 2012, and the latest edition paves the way for the next generation of data-driven risk analysts.

You can buy the book here.

Exploit Prediction Scoring System (EPSS): Good news for risk analysts

Security teams have long relied on CVSS to rank vulnerabilities—but it was never meant to measure risk. EPSS changes the game by forecasting the likelihood of exploitation, giving risk analysts the probability input we’ve been missing.

I'm excited about Exploit Prediction Scoring System (EPSS)! Most Information Security and IT professionals will tell you that one of their top pain points is vulnerability management. Keeping systems updated feels like a hamster wheel of work: update after update, yet always behind. It’s simply not possible to update all the systems all the time, so prioritization is needed. Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) provides a way to rank vulnerabilities, but at least from the risk analyst perspective, something more is needed. EPSS is what we’ve been looking for.

Hi CVSS. It’s not you, it’s me

Introduced in 2007, CVSS was the first mainstream model to tackle the vulnerability ranking problem and provide an open and easy-to-use model that offers a ranking of vulnerabilities. Security, risk, and IT people could then use the scores as a starting point to understand how vulnerabilities compare with each other, and by extension, prioritize system management.

CVSS takes a weighted scorecard approach. It combines base metrics (access vector, attack complexity, and authentication) with impact metrics (confidentiality, integrity, availability). Each factor is weighted and added together, resulting in a combined score of 0 through 10, with 10 being the most critical and needing urgent attention.

CVSS scores and rating

So, what’s the problem? Why do we want to break up with CVSS? Put simply, it’s a little bit of you, CVSS – but it’s mostly me (us). CVSS has a few problems: there are better models than a weighted scorecard ranked on an ordinal scale, and exploit complexity has seriously outgrown the base/impact metrics approach. Despite the problems, it’s a model that has served us well over the years. The problem lies with us; the way we use it, the way we've shoehorned CVSS into our security programs way beyond what it was ever intended to be. We’ve abused CVSS.

We use it as a de facto vulnerability risk ranking system. Keep in mind that risk, which is generally defined as an adverse event that negatively affects objectives, is made up of two components: the probability of a bad thing happening, and the impact to your objectives if it does. Now go back up and read what the base and impact metrics are: it’s not risk. Yes, they can be factors that comprise portions of risk, but a CVSS score is not risk on its own.

CVSS was never meant to communicate risk.

The newly released v3.1 adds more metrics on the exploitability of vulnerabilities, which is a step in the right direction. But, what if we were able to forecast future exploitability?

Why I like EPSS

If we want to change the way things are done, we can browbeat people with complaints about CVSS and tell them it’s broken, or we can make it easy for people to use a better model. EPSS does just that. I first heard about EPSS after Blackhat 2019 when Michael Roytman and Jay Jacobs gave a talk and released an accompanying paper describing the problem space and how their model solves many issues facing the field. In the time since, an online EPSS calculator as been released. After reading the paper and using the calculator on several real-world risk analysis, I’ve come to the conclusion that EPSS is easier and much more effective than using CVSS to prioritize remediation efforts based on risk. Some of my main takeaways on EPSS are:

True forecasting methodology: The EPSS calculation returns a probability of exploit in the next 12 months. This is meaningful, unambiguous – and most importantly – information we can take action on.

A move away from the weighted scorecard model. Five inputs into a weighted scorecard is not adequate to understand the full scope of harm a vulnerability can (or can’t) cause, considering system and exploit complexities.

Improved measurement: The creators behind EPSS created a model that inspects the attributes of a current vulnerability and compares it with the attributes of vulnerabilities in the past and whether or not they've been successfully exploited. This is the best indicator we have that will tell us whether not something is likely to be exploitable in the future. This will result in (hopefully) better vulnerability prioritization. This is an evolution from CVSS which measures attributes that may not be correlated to a vulnerability’s chance of exploit.

Comparisons: When using an ordinal scale, you can only make comparisons between items on that scale. By using probabilities, EPSS allows the analyst to compare anything: a system update, another risk that has been identified outside of CVSS, etc.

EPSS output (source: https://www.kennaresearch.com/tools/epss-calculator/)

In a risk analysis, EPSS significantly improves assessing the probability side of the equation. In some scenarios, a risk analyst can use this input directly, leaving only magnitude to work on. This speeds up the time to perform risk assessments over CVSS. Using CVSS as an input to help determine the probability of successful exploit requires a bit of extra work. For example, I would check to see if a Metasploit package was available, combine with past internal incident data and ask a few SME’s for adjustment. Admittedly crude and time-consuming, but it worked. I don't have to do this anymore.

There’s a caution to this, however. EPSS informs the probability portion only of a risk calculation. You still need to calculate magnitude by cataloging the data types on the system and determine the various ways your company could be impacted if the system was unavailable or the data disclosed.

Determining the probability of a future event is always a struggle, and EPSS significantly reduces the amount of work we have to do. I’m interested in hearing from other people in Information Security – is this significant for you as well? Does this supplement, or even replace, CVSS? If not, why?

Further Reading and Links:

Exploit Prediction Scoring System (EPSS) | BlackHat 2019 slides

Webinar: Predictive Vulnerability Scoring System | SIRA webinar series, behind member wall

EPSS Calculator from Kenna Research

San Francisco's poop statistics: Are we measuring the wrong thing?

Reports of feces in San Francisco have skyrocketed—but are we measuring actual incidents or just better reporting? This post breaks down the data, visualizations, and media narratives to ask whether we’re tracking the problem… or just the poop map.

In this post, I’m going to cover two kinds of shit. The first kind is feces on the streets of San Francisco that I’m sure everyone knows about due to abundant news coverage. The second kind is bullshit; specifically, the kind found in faulty data gathering, analysis, hypothesis testing, and reporting.

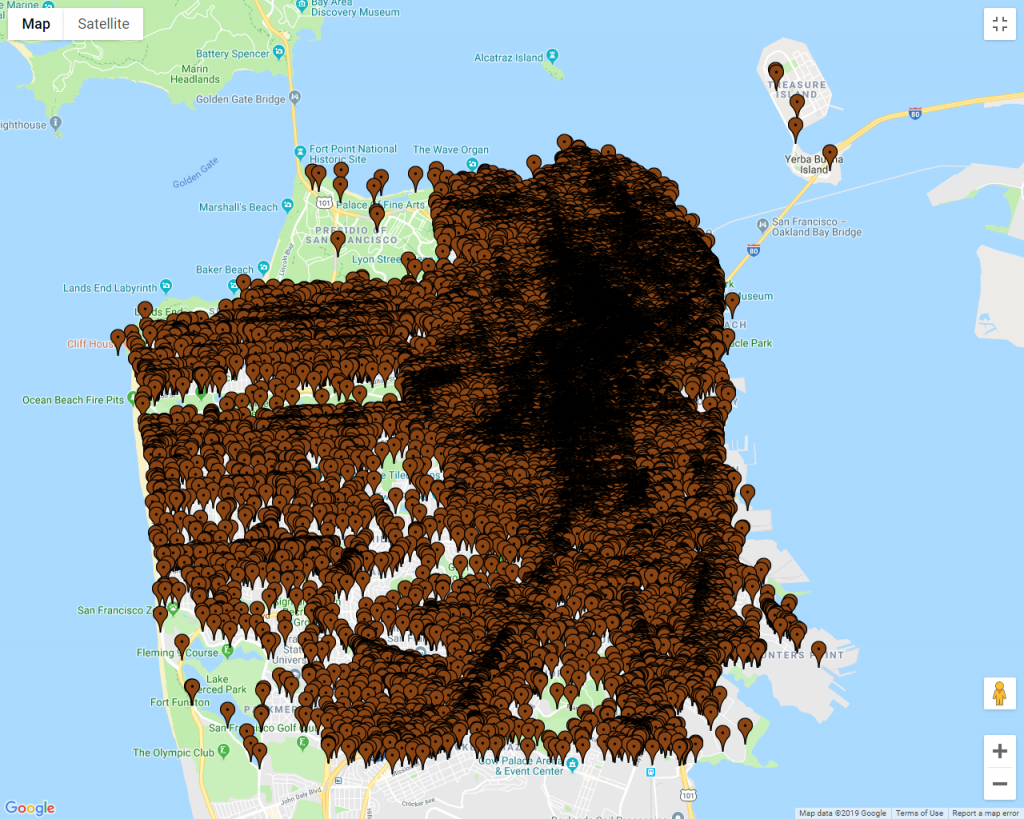

Since 2011, the SF Department of Public Works started tracking the number of reports and complaints about feces on public streets and sidewalks. The data is open and used to create graphs like the one shown below.

Source: Openthebooks.com

The graph displays the year-over-year number of citizen reports of human feces in the city. It certainly seems like it’s getting worse. In fact, the number of people defecating on the streets between 2001 and 2018 has increased by over 400%! This is confirmed by many news headlines reporting on the graph when it was first released. A few examples are:

Sure seems like a dismal outlook, almost a disaster fit for the Old Testament.

Or is it?

The data (number of reports of human feces) and the conclusion drawn from it (San Francisco is worse than ever) makes my measurement spidey sense tingle. I have a few questions about both the data and the report.

Does the data control for the City’s rollout of the 411 mobile app, which allows people to make reports from their phone?

Has the number of people with mobile phones from 2011 to the present increased?

Do we think the City’s media efforts to familiarize people with 411, the vehicle for reporting poop, could contribute to the increase?

The media loves to report on the poop map and poop graph as proof of San Francisco’s decline. Would extensive media coverage contribute to citizen awareness that it can be reported, therefore resulting in an increase in reports?

Is it human poop? (I know the answer to this: not always. Animal poop and human poop reports are logged and tagged together in City databases.)

Does the data control for multiple reports of the same pile? 911 stats have this problem; 300 calls about a car accident doesn’t mean there were 300 car accidents.

Knowing that a measurement and subsequent analysis starts with a well-formed question, we have to ask: are we measuring the wrong thing here?

I think we are!